Bellicose Blathering has added a renowned reviewer for it’s 2014 version of Travels in Reading. If you’re new to this blog, Travels in Reading documents with a mixture of review and reflection the books I’ve read so far this calendar year. Following the unwritten admonition of the internet to “Keep it interesting or I’m clicking on the next sponsored, NSA-informed, targeted ad”, I’ve invited Bartholomew Hughes to write this year’s reviews. He’ll continue in this post until he writes a bad review. Or dies.

Mr. Hughes is known for his strident opinions and his fierce defense of them. He has written many novels, short stories, plays, poems, and other uncategorizable works that he has refused to publish because, in his words, “they’re too good.”

Mr. Hughes is a staunch proponent of the theory that most humans are stupid. A core tenet of this belief is the idea that most readers don’t fully understand what they read, and in recent years Mr. Hughes has embarked on the futile task of setting forth a proper reading of the books he comes across.

A hallmark of Mr. Hughes’ reviews will be his assertion that no book that has ever been published can match those he has written or those that he will write.

It should go without saying, but for legal purposes we will say it: Mr. Hughes’ opinions are his own and do not reflect the lofty and enlightened views of the editors. In fact, we’re not sure why we’ve hired Mr. Hughes, and as far as we’ve been able to tell, his presence on these pages can only be traced to a byzantine trail of bureaucratic snafus.

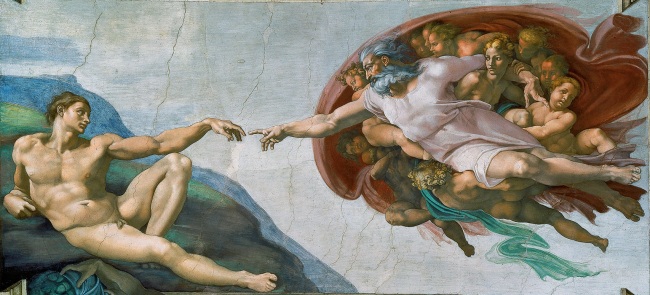

When asked to provide a picture of himself, Mr. Hughes sent this:

Below is his first review, of Ursula Le Guin’s The Dispossessed.

My first order of business before I espouse my views of the detestable Ursula Le Guin novel The Dispossessed is to change the name of this idiotic series. Travels in Reading makes it sound like these posts are a fourth grade teacher’s lame attempts at selling reading to children, or a geriatric’s nightmare blog about traveling in the twilight of what was assuredly a dull life.

I allowed the editors to shoot down my first choice. I suppose The Bartholomew Francis Hughes III doesn’t give potential readers any clues as to what the blog contains. However, it is my firm belief that anything or anyone that takes such a fine name is destined to the upper stratospheres of success.

I’m a huge fan and student of excessive alliteration. So the new title of this series will be Bartholomew’s Bellicose Blatherings about Books. Please do not abbreviate it by using B4 or 4Bs or any such nonsense that cuts out “Bartholomew.”

So Le Guin’s rubbish. Why is it that science fiction writers are hellbent on writing really boring stories? It makes no sense. Here you have a group of people who have the imagination to create stories set in space or on fictional worlds. They’re able to fill in the blanks of these settings so that in the absence of true scientific knowledge, we’re able to “see” these worlds. We’re able to live in deep space on a spaceship with technology that hasn’t yet, or may never be, invented. Why is it that with those powers, some science fiction writers choose to bore us? I feel like while in search of a good time, I wandered into a church led by a pastor with as much life in him as a log.

I did not pick the boring pastor simile willy-nilly. Because Le Guin is definitely preaching a sermon. Perhaps seminary dropouts and those without the moral fortitude to become a preacher fall into science fiction the way a successful, well-known actor ends up doing Sy-Fy channel movies.

The Dispossessed tells the tale of two worlds, Urras and Anarres. Le Guin made up fancy names for Earth and Moon. Urras is the Earth, a place full of “propertarians,” as the book calls them, those that believe in and strive for the ownership of things. Le Guin’s picture of Urras is the classic divide between the Haves and the Have Nots. When Shevek, the main character, visits Urras, he is constantly amazed, and a bit horrified, by the luxury in which those he meets live. I’m sure Shevek would be amazed at the idyllic Hughes manse.

Anarres is inhabited by anarchists. No, not those Molotov cocktail-throwing ruffians who want to banish all laws so they can continue to stop taking baths and smoke marijuana all day every day. But anarchists who believe that laws and government and society impinge on what is most important, the individual’s freedom. According to this point-of-view, an individual’s destiny lies in his own choosing, and any influence upon that choosing by an organized body kills the individuality, the soul of the individual. I don’t have to wonder what my friends at the Club would think of that.

Anarres has a problem though. They’re becoming like the Urrasti, but perhaps worse because they still hold to the anarchist teachings of Odo (a female philosopher from undisclosed years past), or at least think they do, while the machinations of bureaucracy and defined systems of society stealthily steal the soul of the individual. I will grudgingly give Le Guin a compliment for her pointing a finger at human greed – for power, for enlargement of the self – as a primary destroyer of anarchist ideals. I’m going to take a pause here in writing this to go watch Citizen Kane or some other perversion that I can hurl some pent-up invectives at. Complimenting turns me so sour.

Ok, I’m back. That felt good. Really good. Like reading one of my own books. But ok, back to The Dispossessed.

Not much happens in the way of major plot events in this story. The struggle is between ideals, that of anarchism and that of capitalism. And that’s what Le Guin is getting at – the ideals. She often brings up, with no relation to any events in the story, issues of sexuality and clearly points the finger through her heavy-handed prose at what she sees as the restrictive sexual mores of our society, particularly monogamy. She doesn’t completely tear down monogamy and other mores, but she tweaks them so that they fall in line with her anarchist/individualist framework.

So if you want to get preached at about how things ought to be, and bored to tears with a thinly veiled sermon about the evils of an ownership/capitalistic society, then pick up this book and enjoy it.

This concludes my first stellar review for the Bellicose Blathering Newsletter. I agree with you that it was stellar, cogent, and refined. Please visit the site again shortly to read my superb take on Camille Paglia’s Glittering Images: A Journey Through Art from Egypt to Star Wars.

Comments